Boston’s Irish Servants – Taking a Look Back

By: John P. Rattigan

Special to the Boston Irish Reporter – December 2016

It would have been impossible to run a 19th century urban home without domestic servants, and in Boston, that usually included Irish maids. Single Irish women found work as cooks and maids in houses belonging to wealthy families on Beacon Hill in Boston, and in most large American cities

There are many factors to explain how this all came about and, of course, it was the Famine that initiated the mass migration of Irish people. Approximately 1.1 million died and over a million emigrated during the Famine. The population of Ireland plummeted from almost 8.2 million in 1841 to 6.5 million in 1851. Yet, the outward flow continued after the Famine and throughout the second half of the 19th century. The decline of the domestic industry and farming as well as changes in inheritance laws all contributed to draining the country of its “best and brightest.” Between 1850 and 1913, over 4.5 million Irish people left their homeland.

By the mid 1800’s, inheritance laws decreed that farmland would be passed on to the eldest son rather than being divided among all sons. For women, the dowry system is one of the reasons for the drop in population after the Hunger. A woman could only marry if she had a dowry in an arranged marriage and this was reserved only for the eldest daughter. The younger female siblings had fewer options – remain at home as unpaid labor, enter the convent, or emigrate. Even nursing and teaching religious orders required a dowry so, the choice was clear. The main attraction of America was, therefore, work. By 1900, the number of female Irish immigrants exceeded male Irish immigrants. Domestic service was the largest single category of Irish female employment in the United States – approximately 70%.

Most Irish maids were between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five and unmarried. Many lived inside the homes in the servants' quarters and enjoyed a standard of living far better by comparison to the life they had known in Ireland or in the tenement districts. There were advantages – a servant did not need to worry about buying food or fuel for heat, and most employers provided some form of medical care.

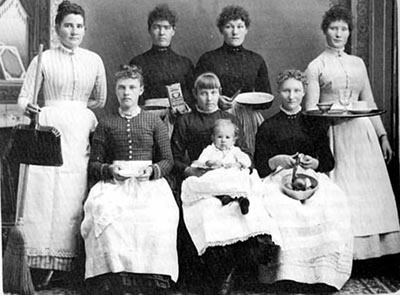

The hours were long and the wages were meager, but these thrifty women always managed to set some savings aside. Often, once settled and employed, a young woman’s first large expenditure was to have a formal photograph taken in a newly purchased frock. This picture was sent home to take a place of honor above the family hearth for all of the neighbors to admire. Moreover, they always managed to save a little money out of their salary for those back in Ireland. From 1850 to 1900, an estimated $260 million poured into Ireland from America, bringing over more family members and helping those remaining behind.

There were also some very poignant and personal stories about these new immigrants to Boston. For several decades in the early part of the 20th century, the Charitable Irish Society employed an immigration agent to assist arriving Irish immigrants on the docks, particularly young, unescorted, women who were vulnerable to being preyed upon. In one monthly narrative report, the agent, Julia C. Hayes, describes meeting 35 ships disembarking its human freight, including several young girls who needed temporary shelter, employment, or assistance in connecting with their friends or relatives. Very often, a few young women were met by their betrothed and many a marriage was concluded within a day of arriving in Boston.

Irish Catholic staff in the service of fashionable Back Bay families appealed to the Archbishop for a church nearer to their live-in employment. In 1888, the Archbishop granted their request and many small contributions allowed the present church, Saint Cecilia’s, to be built in 1894 in the Back Bay. With its predominantly unmarried, female congregation, it was dubbed the “Maids” Church and, unlike any other parish in the archdiocese, few baptisms took place there. In addition, in the warmer months, attendance dwindled as the employers bundled the household staff off to their summer homes in the country or the seashore.

Most women left domestic service when they married and started to raise families. Their stories are the stuff of courage, hard work, and perseverance. They were the “bedrock” of the Irish community back then and an inspiration to the many generations of their Irish-American descendants who followed.